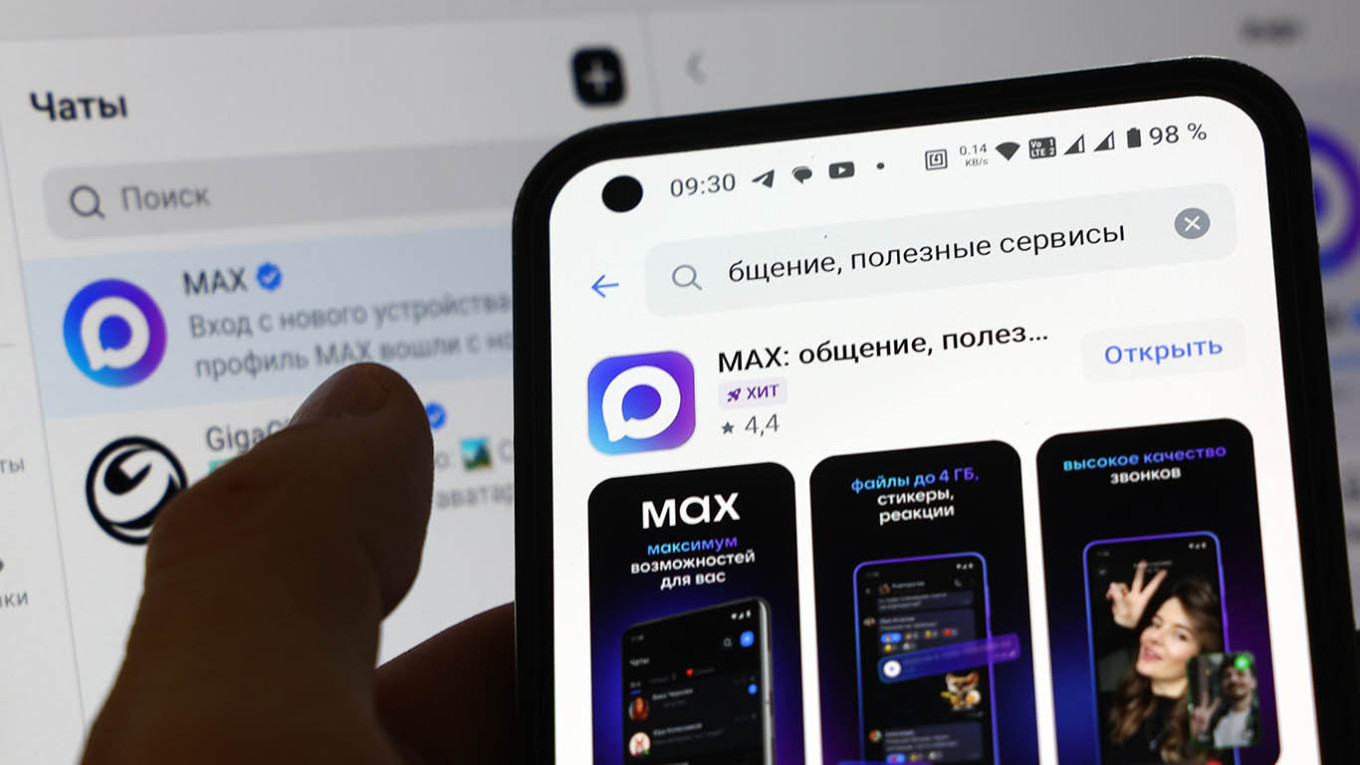

Russia is accelerating its efforts to establish an independent digital ecosystem. Max, a state-sponsored messaging app created by VK, is being marketed as a patriotic substitute for WhatsApp and Telegram—both of which have experienced significant disruptions to their voice and video call features recently.

Officials are setting the stage for Max to evolve into Russia’s “super-app,” which aims to consolidate messaging, payment processing, and government services into one platform.

Since its launch in March, Max claims to have surpassed 18 million registered users, a notable increase from just 1 million in June.

We investigated the app’s features, its vulnerabilities, and the government’s intense push to promote Max as a comprehensive solution:

As of September 1, Max will be required to come pre-installed on all smartphones, tablets, computers, and smart TVs sold in Russia.

The Kremlin’s timing appears deliberate. Since mid-August, users have faced difficulties using WhatsApp and Telegram for voice calls, with many connections failing shortly after initiation.

Roskomnadzor has officially disabled voice calling options on both platforms, citing their misuse by scammers and terrorists, but this has adversely affected ordinary users who depended on these services for economical communication.

“Numerous Russian companies continue to rely heavily on Telegram and WhatsApp for business communication. These [call restrictions] highlight the vulnerability of such dependencies for companies,” said Denis Kuskov, CEO of Telecom Daily, to RBC Life.

Several of Russia’s prominent social media influencers have been enlisted to advocate for Max. Rap artist Instasamka, who has recently started working with the government and has criticized other artists, praised the quality of Max’s calls in an Instagram story, claiming she spoke for two hours in an underground parking lot without losing signal. In a similar fashion, pop artist Valya Karnaval, a VK Video representative, remarked on the app’s “flawless connection, even in a moving vehicle or an elevator.”

Musician Yegor Krid even promoted Max in his music video for “Morye” (“Sea”), where he lays in a rubber boat at sea, expressing: “Can you believe it, Max works even out here!” This overt product placement drew considerable ridicule in the comments.

VK’s design director, Artemy Lebedev, highlighted Max’s lack of anonymity as its key selling point. During a conversation with blogger Amiran Sardarov, Lebedev stated that this feature helps reduce bots and spam. More controversially, he mentioned that he appreciated the absence of “khohly” on the platform, a derogatory term for Ukrainians.

Comedian Denis Dorokhov has also endorsed the app, lauding its connectivity while traveling.

Public sentiment regarding the marketing tactics has been mixed, with streamer JesusAVGN humorously pointing out that Max is merely being lauded for doing its fundamental job, quipping, “With Max, they’ll catch you even in the elevator,” suggesting that like VK, Max might also share user data with authorities.

User reviews vary widely. One Google Play reviewer rated the app one star, stating, “It constantly freezes, and my messages don’t always go through,” while another iOS user gave it five stars, exclaiming, “Finally, an app that just works, unlike WhatsApp. I hope they keep improving it.”

Beyond the flashy marketing, Max is designed to fulfill a governmental role. Authorities aim to integrate it with the state services portal, Gosuslugi, through the Unified Identification and Authentication System (ESIA). This would enable users to access government services, pay utility bills, or sign documents directly via Max, effectively turning it into a digital gateway for essential public services.

However, during an official meeting in early August, the Federal Security Service (FSB) initially blocked Max’s integration with ESIA over concerns about potential data breaches. Reports from the IT sector indicated that the FSB presented a lengthy list of demands, including certified encryption protocols and source code evaluations. Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Grigorenko, who is overseeing the project, echoed these concerns.

As of August 7, Digital Development Minister Maksut Shadaev announced that Max had met the security criteria set by the FSB for integration with Gosuslugi. VK claims they are addressing any ongoing issues, though full integration is anticipated only by late autumn.

Currently, Max resembles any standard chat application, lacking noticeable additional features, and the integration of government services is not yet apparent.

Despite the absence of full access to Gosuslugi, governmental agencies are aggressively promoting Max to the public. Moscow’s Ministry of Housing and Communal Services has mandated the transition from WhatsApp and Telegram to Max for all building and neighborhood discussion groups. Yevgeny Stupin, a former deputy in the Moscow City Duma, stated that the directive originates from the Construction and Housing Ministry. Flyers instructing residents to download Max are popping up in apartment building lobbies across major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg.

In Bashkortostan, housing management companies were given a deadline of August 25 to migrate all resident discussions to Max. Similar directives have been sent to management companies in various regions, including Moscow, Tula, Nizhny Novgorod, Krasnodar, Belgorod, and Bashkortostan, as reported by Ostorozhno Novosti.

Educational institutions across over 20 regions are also being compelled to adopt Max. Regions like Tatarstan, Mari El, and Altai, along with the Khanty-Mansi autonomous district and the Vladimir and Tver areas, are piloting a project to transition all school communications to Max. Tatarstan officials announced that Education Ministry personnel, school and kindergarten leaders, students, and their parents are required to switch to Max by November.

A teacher from Tatarstan expressed anxiety to the exiled news outlet Vyorstka about potential pressure from authorities to conform again.

“They’ll probably once again pressure us to persuade students and parents [to use Max],” said the teacher.

“At work, we were informed that soon we all must switch to Max. They didn’t clarify what that entails or whether refusal is an option. Knowing that Max serves as a state monitoring tool, I’d really rather avoid it,” a 63-year-old pediatrician in St. Petersburg, who requested anonymity, told The Moscow Times.

According to Vyorstka, at least 57 regions are mandating that public-sector employees and officials transition to Max, affecting schools, housing services, and local governance. St. Petersburg State University has claimed to be “the first university in Russia to commence using the national messenger,” while the governor of St. Petersburg declared it the first region to use Max for municipal services.

Max’s rapid expansion has revealed its vulnerabilities.

After VK launched a public bug bounty program in July, security researchers uncovered numerous critical vulnerabilities within weeks. VK reported disbursing over 220,000 rubles (approximately $2,700) in rewards, now offering up to 5 million rubles ($62,000) for discovering significant security flaws—a move that reflects the risks of hurried development and the pressing need to resolve these issues.

Max can only be registered using Russian or Belarusian phone numbers, blocking virtual SIM cards and making registration from abroad impossible. This effectively prevents Russians living outside the country from connecting with friends and family in Russia via Max unless they manage to obtain a Russian or Belarusian number.

An independent analysis recently characterized Max as highly intrusive, revealing its collection of IP addresses, geolocation data, and contact lists, with its privacy policy clearly indicating that such information may be shared with governmental entities and “company partners.” The app also requests permissions for access to the phone’s camera, microphone, Bluetooth, notifications, and biometric features. Developers depend on open-source code from foreign countries, including Ukraine, which critics assert undermines Moscow’s claims of technological independence.

Security experts have documented scams targeting Max users, where fraudsters impersonate technical support and offer bogus “protection activation” services to deceive victims into divulging their SMS verification codes.

Social media is rife with memes comparing Max to “mandatory Soviet-style queues,” humorously suggesting that “Max will soon be pre-installed on our kettles and refrigerators.” Users are mocking its bugs, sharing screenshots of stalled chats with captions like “sovereign technology at work.” On X, one user quipped, “Max works even at sea—but not in my kitchen.”

“Public-sector employees in Russia are among the most powerless, akin to migrant workers, so they will comply with any ridiculous demands from higher-ups,” said blogger Anatoly Nesmiyan.

This humor underscores a pervasive anxiety: people may download Max due to pressure, but they seem reluctant to embrace it willingly.

Max’s emergence embodies Russia’s digital aspirations and its underlying insecurities. The app is backed by celebrities and enforced through state mandates, while foreign alternatives encounter increasing technological limitations.

The future of Max—whether it evolves into a trusted everyday tool or remains a marker of state coercion—hinges on VK’s capability to address security vulnerabilities as well as the public’s willingness to adopt it beyond mere obligation.

Importantly, authorities are not abandoning earlier digital projects but amalgamating them into Max’s framework.

Sferum, the state-operated educational platform that integrates messaging with online learning tools and has been compulsory in schools since 2022, is being merged into Max. The Ministry of Education announced that Sferum’s functions will start being integrated into Max in the upcoming school year, with pilot regions initiating on August 25 and nationwide availability by September 15. The Sferum website now prompts users to download Max to access its offerings through the national messenger.

As one educator from the Vladimir region noted regarding the earlier Sferum implementation: “We registered for Sferum because it was mandatory, but we still communicated via other messaging apps.” This trend may repeat with Max: superficial compliance may hide ongoing dependence on foreign platforms—at least while they remain operational.

The push for Max tests Russia’s ability to exert digital sovereignty through administrative control rather than through technological advancements.

With WhatsApp and Telegram voice calls currently disabled, millions of Russians are faced with a stark dilemma: adopt a messaging app they do not trust, or sacrifice easy communication with friends, family, and colleagues.

As the deadline for mandatory pre-installation looms and regional mandates intensify, Max may find success not through genuine consumer interest, but due to the lack of alternatives.