Hello and welcome back to The Long Wave. This week, I had a conversation with acclaimed filmmaker and poet Caleb Femi about his newest collection, The Wickedest, which takes readers on a chronologically structured journey through an imagined house party in South London. But first, let’s dive into the weekly highlights.

DRC conflict intensifies | The armed faction M23 and Rwandan soldiers have taken over Goma in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, heightening concerns of a larger conflict brewing between Rwanda and DRC. As reported by Carlos Mureithi, the violent upheaval in eastern DRC compounds the issues facing a nation already grappling with one of the most severe humanitarian crises globally.

Families of apartheid victims pursue legal action against South African government | The families of the Cradock Four, a group of anti-apartheid activists killed by state security forces in 1985, are now seeking justice from the South African government for its failure to hold the perpetrators accountable.

Removal of Black airmen from US Air Force curriculum | Due to Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at dismantling diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, the US Air Force has paused a training documentary about the famous Tuskegee Airmen, the first African American pilots trained in the military.

Sierra Leone stands at the brink of significant reform | A proposed parliamentary measure could result in the repeal of an antiquated British colonial statute, paving the way for the legalization of abortion and guaranteeing comprehensive reproductive rights for all women and girls. Yet, progress faces potential setbacks from the influence of US religious extremists.

Recognition of Afro-Brazilian stories in cinema | The film production company Filmes de Plástico has concentrated on producing stories centered around working-class, urban Black characters, who remain largely underrepresented in Brazilian film.

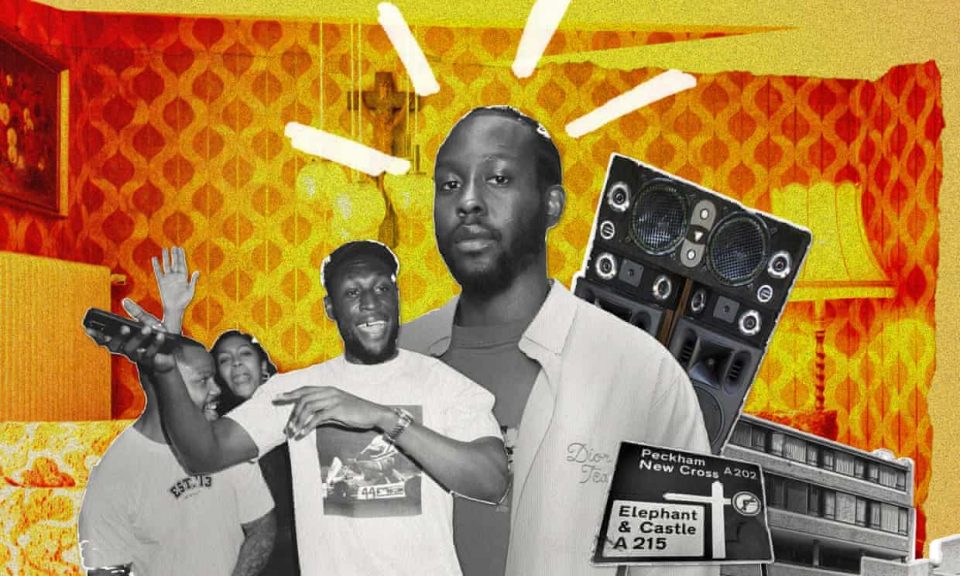

The Wickedest portrays a legendary, monthly house party in South London that spans three generations—an Uber driver shares the lore of this gathering, which begins with a man named Mig Jarrett, who danced joyfully after falling for “someone’s aunty”. “The wickedest / people who / geese-flocked / to Mig’s / house claiming / bomb shelter.” For Femi, 34, this collection was inspired by his upbringing in a now-demolished estate where house parties and “shoobs” served as a necessary escape from the hardships faced by working-class Black communities in inner cities.

Notorious for the tragic murder of 10-year-old Damilola Taylor in 2000, the North Peckham estate was like many postwar concrete housing projects, intended to provide stability to Britain’s marginalized populations, but instead became synonymous with crime and deterioration. These narratives have been previously explored in Femi’s debut collection, Poor. He describes The Wickedest as being “intimately connected to the world of Poor, yet it captures moments of celebration in contrast to the adversity faced by the same individuals portrayed in Poor.”

Certainly, The Wickedest immerses readers in the joy of the gathering. The text dances through a rhythm shaped by the passage of time. At 11:03 pm, guests arrive, donned in “Amina Muaddi heels and B22s”; at 01:42 am, the DJ reprimands a couple caught “lipsing” (British slang for kissing) by the window, saying, “you lot been there all night though / you’re blocking the breeze.” By 03:26 am, a partygoer is in tears mourning a lost friend: “My gut tells me that you are here … / you’ve never been the type / to miss a lit shoobs.” For Femi, the essence of a house party lies in how time influences our emotions and experiences. “Certain feelings only manifest due to the hour of the night,” he reflects. By navigating the timestamps in The Wickedest, readers encounter insights into “hood peacocking” (trying to impress attractive individuals) and learn the “destruction dance,” all while experiencing genuine human emotions, as romances flourish and falter, the party becomes a haven for escape, and characters share wisdom amongst themselves. Femi “felt that the timestamps would enable the reader to get involved” and that the diverse cast of characters allows for “space to connect with what resonates with them.”

A rich legacy of celebration amidst struggles

The inspiration behind The Wickedest stems not only from Femi’s experiences as an adult party-goer but also his childhood spent on a social housing estate. “Growing up on the North Peckham estate around age 10 was my introduction to communal house parties.” These gatherings were welcoming—if you were a resident, you were part of it, with doors left open. “I remember the sounds of music from different floors, witnessing excitement and knowing I could join in, seeing other children from the estate coming and going.”

Femi would sneak past his parents to attend these lively events and found that they reflected the diverse migrant communities cohabiting the estate—Femi himself had arrived from Nigeria in 1997 at the age of seven. “There were distinctly West African parties featuring fuji music or P-Square tracks. Then there were the Caribbean celebrations that intrigued me with their lovers rock tunes—music I never experienced at home. I also enjoyed reggae’s infectious energy. I could see the parallels with Nigerian beats.” Additionally, there were the sounds unique to Black British culture: garage, jungle, and rave, which thrived on pirate radio. Whenever kids from the block hosted parties, the playlists featured tracks from S Club 7 and the Cheeky Girls, echoing primary school disco vibes.

Femi is keenly aware of the historical significance of such gatherings within Black communities in Britain. He explores how communities marginalized and enduring hardships sought refuge in these celebrations. He describes his fascination with shebeens—the unlicensed bars and house parties that thrived in postwar Britain. “I spoke with three Caribbean women from South London in their late 60s who recounted how shebeens would pop up in garages, vacant spaces, or someone’s home.” Such underground festivities, also referred to as blues parties, were born from West Indian migrants sidelined by the “colour bar” in mainstream clubs.

However, Femi acknowledges that these treasured gatherings were often impacted by external prejudice. “There was a persistent belief that illicit activities transpired there, reflecting how society tended to view working-class Black communities as dangerous.” Such dehumanizing stereotypes regarding Black gatherings have surfaced during pivotal moments in British history. The devastating New Cross fire in 1981 claimed the lives of 13 young Black individuals at a house party while celebrating an 18th birthday. Although it was never conclusively determined to be a racially motivated attack, it has been established that the fire was set intentionally, following complaints lodged with the police about the party.

The decline of Black nightlife

At the heart of The Wickedest lies a copy of form 696, a risk assessment utilized by the Metropolitan police to gauge potential violent crime at music events. When asked about the venue’s maximum capacity, Lala, the host of the Wickedest, humorously notes: “Unknown (it was built by the same architect as the Tardis).” Form 696 was enforced across 21 London councils from 2008 to 2017, seen as a veiled attempt to stifle Black nightlife by revoking the licenses of Black-led grime and garage venues, with an extended version of the form even inquiring whether a specific ethnic group was anticipated at events. Femi incorporated this element to highlight how licensed venues evolved from house parties and how Black individuals have faced ongoing police scrutiny, often due to “noise complaints” at each stage of nightlife’s evolution. In Sonnet 696, he writes: “What could possibly go wrong if we all end up under one roof; a party, / summer barbecue, will we all combust?”

The vulnerability of Black nightlife is a significant theme throughout The Wickedest. Femi observes that house parties have evolved, primarily due to the decline in social housing and the dwindling availability of appropriate venues. He reflects on the absence of character in contemporary housing designs. Modern constructions with sleek white kitchen countertops lack the personal touches and cultural artifacts that once defined early house parties, leaving such memories to exist in nostalgia. While Stormzy’s house party venue in Soho attempts a close visual replica, it lacks the authentic essence of what once was. In The Wickedest, however, Femi encapsulates the true spirit of the house party—an amalgamation of noise, complexity, and the beauty and history that surface when Black individuals gather in pursuit of joy.

The Wickedest by Caleb Femi is published by 4th Estate (£14.99). To support The Guardian and Observer, purchase your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery fees may apply.

To get the full version of The Long Wave in your inbox every Wednesday, subscribe here.