Friday, February 28, 1975, marked a pivotal moment in my life. That morning, at 8:30, I was preparing to compose a feature for a newspaper. By 9:35, I found myself in the press area outside Moorgate station.

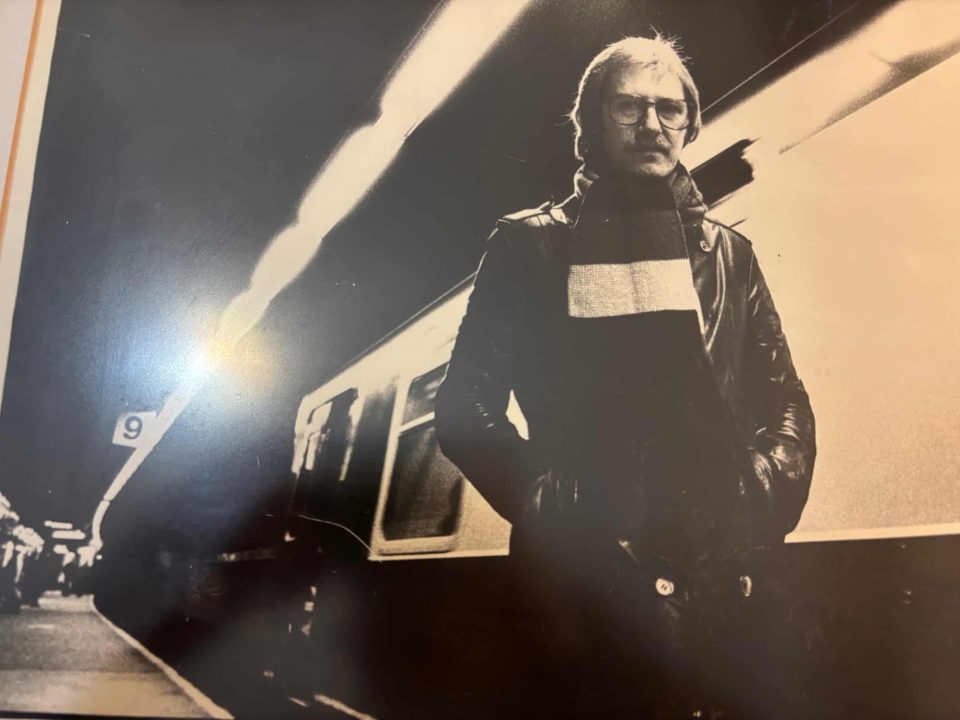

At just 25, I was a freelance journalist, occasionally reporting on news stories for a Fleet Street agency, but I had never been assigned to cover an event as significant as the Moorgate train disaster. My task was straightforward: uncover the details concerning what happened, who was involved, when it occurred, and how it transpired. We already knew the location, and upon arriving, I noticed a small group of ten journalists confined to the area near the underground station’s entrance. A mere thirty minutes later, the first of many press briefings commenced. I had my shorthand notebook poised and ready.

“Good morning. I’m Brian Fisher, overseeing disaster planning for the City of London police. At 08:46, a serious incident took place when the three front carriages of an underground train collided with a dead-end tunnel. The force of the impact forced the first two carriages upwards, with the driver’s cabin lodged in the tunnel’s roof. We fear there may be around 40 individuals trapped within the train…”

I remained at Moorgate station and later at Barts hospital, gathering accounts from the injured until shortly after noon, at which point I sent my report from a nearby phone booth. The editor on duty praised my effort and advised me to head home and submit my invoice. While I wished to continue with the story, I recognized that this was evolving into a significant news event, one that would likely be handled by a more seasoned reporter. Unbeknownst to me as I submitted my report, my father lay 60 feet below the pavement at Moorgate station, having lost his life instantly when the train struck the concrete wall.

My dad, a 68-year-old retired police officer, was on his way to work at Liverpool Street that day. If only he had succeeded in finding a parking spot close to Finsbury Park station, where he dropped off my stepmother, he would have taken the Piccadilly line, then transferred to the Central line to reach his destination. However, due to a lack of parking spaces, he opted for nearby Drayton Park station, where he changed at Moorgate station to get to Liverpool Street. The absence of parking at Finsbury Park cost him his life.

The Moorgate train accident would become the most significant catastrophe in the City of London since the blitz, claiming 43 lives and injuring nearly 80 more. By 4 p.m. that day, over 100 reporters, photographers, and film crews from around the globe crowded around the entrance of the station.

Being Jewish, my father was the first victim to be buried, just a day after his body was retrieved from the mangled second carriage. On that frigid Sunday morning at the cemetery gates, I encountered numerous journalists and reporters, and I took it upon myself to ask them to honor my family’s need for privacy during this painful moment—I explained that I too was a journalist, and this was an incredibly heart-wrenching occasion for me. They honored my request, and one reporter from the Sunday Times seemed to take note of my plea and relayed it to his editor.

Five days later, I was brought on board by the renowned Insight investigative team at the Sunday Times, led by Harry Evans. Why would such a prestigious publication hire a newcomer? Because Evans believed that the relatives of the deceased, along with the transport secretary, police, and anyone else connected to the disaster, would be more inclined to speak with a journalist whose own father had fallen victim.

Evans’s instinct proved to be correct. My personal loss opened doors that might have otherwise remained shut. I quickly realized the challenge before me: could I separate my grief from a comprehensive investigation into the crash’s causes? I soon understood that intertwining my personal feelings with my professional duties could hinder me from fully embracing this unique opportunity. I found I could leave each morning, leaving behind the photo of my father; he belonged at home, while I was to operate in the sphere of investigative journalism.

For the next fifty weeks, I interviewed every key player in the tragedy, family members who lost loved ones, and even some conspiracy theorists—yes, even in those early days. The access I gained was astonishing. With a simple introduction of, “This is Laurence Marks from Insight, the Sunday Times,” officials who were previously “unavailable,” “on holiday,” or “in a meeting” suddenly became very responsive. Everyone, that is, except for London Transport, who was keen to avoid any involvement in potential compensation claims. Ultimately, only a few claims inquiries occurred, with, to my recollection, just a single payout.

I attended the coroner’s inquiry six weeks post-disaster and dedicated three days to listening to the evidence. Dr. David Paul, the City of London coroner, presented the jury with four potential conclusions regarding the driver’s actions: manslaughter, accidental death, suicide, or an open verdict. The jury concluded it was accidental death, but in a private conversation with Dr. Paul weeks later, he confided in me that I should investigate the possibility of suicide. He believed the evidence pointed in that direction but felt unable to guide the jury without a note from the driver.

The interview I most desperately sought (as did every other journalist) was with the driver’s widow, Helen Newson. I had penned letters to her multiple times, but, unsurprisingly, received no responses. However, a week before my Moorgate story was slated for publication, I decided to take a chance. I traveled to the south-east London council block where the Newson family resided and left a handwritten note expressing my eagerness to speak with them, mentioning that I would be waiting in my car.

Forty-five minutes later, I heard a tap at my window. There stood a young woman who conveyed that her mother wished to speak with me. As a journalist, I gained insights that no one else had, but Mrs. Newson could not provide any clearer understanding of what had driven her husband to act than I could. Her pain was palpable, and she repeatedly apologized for her husband’s actions, to which I reassured her that she was not to blame and had nothing to be sorry for.

When I penned my Insight feature, it carried the headline: “Was It Suicide?” The truth is, we may never know. The driver left no note, which rendered any concrete evidence absent. London Transport’s chief engineer informed me that the train involved in the accident was in flawless condition, emphasizing that the driver could have applied the brakes at any moment to halt the train. He noted, “The driver operated the train normally at every stop that morning, with the exception of Moorgate. He could have applied the brakes but chose not to.”

I dedicated several days with esteemed pathologist Prof. Keith Simpson, who walked me through the postmortem examination of the driver. He concluded that there was no medical condition found that would have prevented the driver from releasing the “deadman’s handle” (the spring-loaded brake). Prof. Simpson firmly stated that the driver had not experienced a stroke, heart attack, blindness, seizure, or electrocution. He simply failed to apply the brakes, even accelerating the train as it approached the daylight of Moorgate station.

When my article was published, I faced criticism from some quarters for even insinuating that the driver may have opted to end his life and, by extension, the lives of others. I felt it was time for me to step back and allow the matter to be put to rest. Yes, I had lost my father, but nothing I wrote—despite tempting offers for television appearances, radio segments, or even a book deal—could bring him back. My year-long investigation elevated my journalistic career, and I believed that my future was taking a promising turn. I wrote for national newspapers and contributed to the ITV current affairs program, This Week. I could have reasonably thought I was on a path leading to becoming a prominent television reporter.

But comedy intervened.

For years, I had been secretly composing comedy sketches and half-hour sitcoms, all of which had been rejected, albeit with positive feedback. In 1977, my writing partner, Maurice Gran, and I were tasked with creating the Frankie Howerd Variety Show, marking the start of a television comedy career that produced programs like The New Statesman, Goodnight Sweetheart, Shine on Harvey Moon, and Birds of a Feather. One psychiatrist suggested to me, “Perhaps you’re using comedy to overshadow the tragedy of the Moorgate train disaster.” Who could dispute that possibility? Regardless of the reason, my career in comedy took off, and the Moorgate disaster faded into the recesses of my life and memory.

In 2006, I was featured in a Channel 4 documentary titled Me, My Dad, and Moorgate, which focused more on my television endeavors than the disaster itself. Subsequently, the dusty records concerning Moorgate were archived at my university. Then, in 2023, Maurice cautiously proposed that I review the mountain of old research documents and perhaps develop a drama about that transformative day in February 1975. My first response was: “Why would I want to relive the agony of losing my dad in a train carriage crushed down to just 15 feet?” Maurice and our manager presented a compelling argument, and when I finally acquiesced, the next question arose: for which medium would we create it? After thorough discussions, we decided on radio.

Maurice and I collaborated to recount the events of Friday, February 28, 1975, in two parts: the first from the perspective of the rescue teams outside the wreckage, and the second from within the front carriage, spotlighting the last two survivors who were trapped for an agonizing 12 hours. I employed my extensive library of resources: cassette-recorded interviews, shorthand notes, and documents I shouldn’t have received in the first place. We then assembled the content for two 45-minute plays, set to air on Radio 4 later this month.

The two pieces were crafted and finalized in 2023, then refined the following year when additional information surfaced from those who discovered the project through social media. Ambulance personnel, doctors, firefighters, and London Transport engineers came forth to share their experiences and involvement. This feedback was invaluable; it enriched our narrative and transported me back 50 years to that press enclosure at Moorgate station.

As I reflect on my younger self—the journalist who, it could be said, found his footing in the field while losing his father—I ponder whether I would embark on that journey again. Without hesitation, I would. I was fueled by ambition, and I believe my actions were justified. In many ways, it served as a form of therapy for my grief. Each day unveiled new insights about my dad’s life and the true events of that fateful day.

While I found solace in my published article and the process leading to it, that was not the case for Helen Newson, whose family was upset by my suggestion that her husband, the father of her daughters, may have died by suicide. The opinions of other victims’ relatives were divided; some expressed gratitude for my effort to uncover the circumstances surrounding their loved ones’ deaths, while others were angered by my intrusion into their suffering.

How do I feel about revisiting the past? It was unsettling to relive the experience of my younger self, conducting interviews with significant figures in the event (most of whom are now deceased), and examining my theories regarding that morning in 1975. Yet, had the train arrived as scheduled at Moorgate station, allowing all passengers, including my father, to disembark and continue their day, I can express with confidence that my life would have taken an entirely different course.

*Moorgate will air on Radio 4 on February 26 and 27 and will also be accessible on BBC Sounds.*