They ventured into 1980s London with modest aspirations: to pursue education, seek employment, escape their past, and possibly return home one day. A significant number of individuals arrived from Nigeria, often laboring during the night, juggling two jobs alongside part-time studies, caught in an endless cycle of early morning shifts, lectures, and nocturnal work, all in hopes of earning a qualification that would lead to a stable career.

Many of us grew up hearing these accounts—our parents toiling in low-profile jobs for years, cleaning offices in the towering glass edifices of Canary Wharf before dawn, then serving meals in Soho and Knightsbridge during summer evenings. Relatives and elders made their living in local bowling alleys, bingo halls, cinemas, hospitals, and care homes, moving through a vast, looming city while maintaining a low profile.

My father, who worked in various restaurants while studying at a nearby polytechnic, lived in Southwark and later in Lewisham, becoming part of a slowly expanding community of Nigerians throughout the city. They formed close-knit neighborhoods for their collective survival, seeking solace in one another, and attempting to adapt to unfamiliar environments in hopes of making London feel like home. By the turn of the millennium, approximately 90,000 Nigerian-born individuals had settled in the UK, yet they often remained invisible in the broader national narrative.

This narrative intertwines with football and the theme of belonging within the city’s very essence, but to unfold it adequately, we must first revisit the backdrop of conflict. Our experiences in the diaspora originate far from the streets of London. The years between 1967 and 1970 are etched in history as the Nigerian civil war, also known as the Biafran war, a harrowing quest for freedom and integrity. The roots of this conflict trace back to the horrors of the colonial era. Our existence is intertwined with the violence that gave rise to Nigeria, bearing the scars of an empire etched into its very identity. The British first set foot in the region during the 17th century, gradually extracting its riches and basking in its gold. By the early 1900s, the empire had delineated lines across West African soil, extending from the southern coastal and rainforest areas inward to the Sahel savannahs in the north, uniting over 400 ethnic groups, each with their distinct languages, cultures, and identities, into one entity. Britain dubbed this sprawling new creation the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria.

This amalgamation was fraught with tension. In 1960, when Nigeria finally gained independence from Britain, the Colony and Protectorate ceased to exist, giving rise to a new nation. However, ethnic strife persisted. Those years of civil conflict are remembered as a genocide, with estimates suggesting the loss of 3 million lives, half of whom were children, resulting from gun violence, starvation, and brutality. Some sought refuge in Britain while others endured the violence in Nigeria.

The aftermath of war leaves indelible marks. Its shadows linger in memories, mass graves, and the painful realization that a nation can fall apart and decent individuals can commit heinous acts. Against the backdrop of ongoing turmoil and political unrest, many opted to migrate to London, a wave of movement that surged in the 1980s when the global oil market plummeted, plunging Nigeria into an economic crisis. My father and many others were part of this diaspora, linked by the colonial history that intertwined their fates.

Nigeria’s burgeoning presence in London has also paralleled the evolution of England’s national sport, football. Since its inception, the Premier League has mirrored the social transformations within London’s diverse neighborhoods. The city reflects its people and communities, echoing Britain’s ties to the world, the remnants of colonial history, its fractured relationships with Europe, and its dual role as a hub for global finance and a refuge for asylum seekers. As Nigeria’s war generation emerged, their integration into English football felt inevitable.

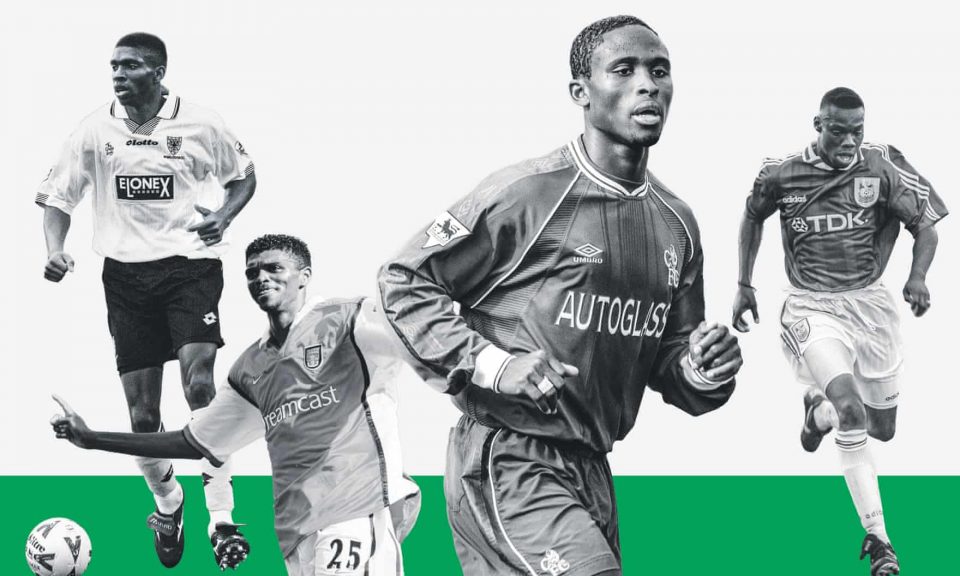

In November 1992, a 17-year-old George Ndah, born in Camberwell to Nigerian parents, made his debut for Crystal Palace at Anfield, marking a pivotal moment in Premier League history during its inaugural season. That day, he became the youngest player in Crystal Palace’s Premier League framework. He was not alone; Efan Ekoku, also of Nigerian descent but born in Manchester, appeared in that first season while playing for Norwich before relocating to London to join Wimbledon for five seasons. Both players were later called up to represent Nigeria, embodying the dual identities of British-Nigerians as the city opened its doors to the world.

The Nigerian national squad that triumphed in the 1994 African Cup of Nations represented a golden generation. This era emerged amidst continued political turmoil and violence; a military coup in June 1993 toppled Nigeria’s interim government, returning the country to dictatorship—a scenario that had played out repeatedly in the preceding decades.

Under the guidance of Dutch manager Clemens Westerhof, a young cohort of footballers was assembled, forming a team that continues to shape Nigeria’s footballing legacy, both for those at home and for those raised in London. After sealing their African Cup of Nations victory in Tunisia, players like Jay-Jay Okocha, Rashidi Yekini, Sunday Oliseh, and Stephen Keshi helped Nigeria qualify for the 1994 World Cup in the United States, reaching the knockout stage. Two years later, in the 1996 Olympics, they triumphed over Brazil and claimed victory against Argentina in the finals.

In the wake of this international acclaim, several core members of this exceptional generation followed their compatriots to London. Olympic captain Nwankwo Kanu joined Arsenal from Inter Milan in 1999, while Celestine Babayaro signed with Chelsea in 1997. Others landed opportunities at clubs outside London—Jay-Jay Okocha at Bolton in 2002, Finidi George at Ipswich in 2001, while Taribo West and Daniel Amokachi joined Derby and Everton in 2000 and 1994, respectively.

To many English fans who followed these teams weekly, these players were merely footnotes in a long-standing narrative. Yet for those who had immigrated from Nigeria to London, these footballers were representatives of their homeland, providing a first glimpse of familiar faces in the landscape of mainstream British culture.

I was around two years old as that golden generation emerged, too young to witness it unfold directly. However, their stories became heirlooms passed from father to son—vague recollections of an uncle’s friend’s classmate who played alongside Kanu in Nigeria, or of a squad member who shared our heritage. They reflected our lineage and identity. Football and its players shaped our childhoods in such profound ways, becoming a steady presence in our formative years and anchoring us to this new land.

My youth is threaded with these memories, moments and traditions that helped me forge my identity. Uncles and family friends gathered in the living rooms of council flats in Lewisham and Peckham, watching Kanu in FA Cup finals and Premier League matches, collectively frustrated whenever English commentators mispronounced his name, just as teachers would often do to ours. One afternoon, my father spotted Kanu while driving near the Thames and excitedly honked his horn, waving at him, and I recall Kanu acknowledging him back. It was a moment of recognition shared by two countrymen in a bustling metropolis.

There’s a memory of waiting outside Stamford Bridge for an uncle who worked as a security guard there—so faint that I sometimes wonder if it actually happened. The only certainty is the awareness that my uncle was employed at the same club where Babayaro played, instilling a feeling of unity among our Nigerian community spread throughout the area.

In recollecting those formative years, our connections to our roots remained vibrant through calls and letters exchanged with family in Nigeria, reaching our rarely seen grandparents and elders. Our forebears left an imprint on the city, recreating home through the traditions they preserved. In the monthly gatherings held in family living rooms and community centers at Elephant and Castle, during christenings and holy communions across the city, and at summer parties in Bermondsey lasting until dawn, we shared meals and conversations in the language of our ancestors. The music that filled our homes and the politics discussed when the night turned serious contributed to our sense of identity.

I knew Nigerians from various parts of this city, immersed in a belief that there was no division between us and the events occurring thousands of miles away; we felt more connected to “that” reality than to this one. England felt like an afterthought, a distant land overshadowed by the nurturing embrace of our community.

Our sense of national identity runs deep, serving as a vessel for discussions about heritage, community, political realities, and acceptance. Within these dialogues, football often occupies a central space in the narratives we’ve been told and continue to share.

I can trace my own childhood feelings of belonging through this lens. My initial encounters with international football were lacking the jubilant celebrations intertwined with England’s collective memory. I feel little connection to iconic moments like David Beckham’s free-kick that secured England’s qualification for the 2002 World Cup or Paul Gascoigne’s memorable goal against Scotland in the same year—both events I learned about long after they had transpired. I have no recollections of the celebrated 5-1 victory over Germany in Munich or of England’s participation in Euro 2000.

We lived in our own distinct narrative. The Super Eagles were our compatriots—a team whose tales and legacies were deeply ingrained in our upbringing. The first international football jersey I remember owning was a replica from Nigeria that my cousin brought from Lagos, proudly adorned with a misspelled version of my name.

This sense of separation emerged during interactions with the broader world. I recall the 2002 World Cup held in Japan and South Korea, where Nigeria faced England in their final Group F match. That game was screened at our primary school’s assembly hall with lessons canceled so everyone could watch. Students and teachers made their way to gather around a TV. As the match commenced, my brother and I cheered for Nigeria’s green-clad players, the only two in the hall doing so.

I also remember the Unity Cup in 2004, held at Charlton’s ground, The Valley, where Nigeria played against Ireland and Jamaica to celebrate the three countries with significant diasporas in London. My father, my uncles, their children, and a sea of other Nigerians filled the stands, waving flags in encouragement whenever Nigeria made strides on the field. That was my first experience of live international football, enveloped by the essence of Nigeria as I understood it, defined by a homeland I had yet to visit.

As the new millennium dawned, the Nigerian community had been a part of London for decades. Yet representation in the England national team remained elusive. John Salako, who spent much of his career in south London at Crystal Palace and Charlton, received five caps for England in 1991. The late Ugo Ehiogu from Hackney played four friendly matches between 1996 and 2002, while Wimbledon striker John Fashanu participated in games against Chile and Scotland in 1989. Fashanu later expressed his regret about not playing for Nigeria, lamenting that despite his desire to represent his home country, he was never selected for the national team apart from one friendly match.

Some individuals raised in London continued to don the Nigerian jersey. Danny Shittu, born in Lagos yet brought up in East London, and brothers Efe and Sam Sodje, also from south London, with roots in Warri, Nigeria, both played for Nigeria. Their younger brother Akpo aspired to international play, declaring once, “My dream is to be my country’s No 1 striker.”

When I came of age, the glorious days of Nigeria’s illustrious generation had long since passed. Nigeria did not qualify for the 2006 World Cup and exited in the group stages of the tournaments in 2002 and 2010. The African Cup of Nations yielded a lone victory in 2013 and failed to produce qualifications in 2012 and 2015. John Obi Mikel, touted as Nigeria’s golden boy who was expected to restore creativity to a beleaguered national team, joined Chelsea in 2006. Under José Mourinho’s leadership, he became a disciplined, ultra-efficient defensive player, embodying the frustration of what could have been and the disappointing reality that prevailed for many fans.

The 2023 African Cup of Nations team included five British-Nigerians: Alex Iwobi, the nephew of Jay-Jay Okocha, grew up in Newham, along with defender Calvin Bassey. Ademola Lookman, Ola Aina, and Semi Ajayi hail from the southern part of the city. They represent a new wave of players eager to align themselves with Nigeria, dubbed the “innit innit boys,” a term that affectionately references their British accents. In discussing the choice to represent Nigeria, Iwobi remarked, “I always felt at home in England but more connected to the west African nation.”

These players played a vital role in guiding Nigeria to its first tournament final in a decade, reflecting a blend of Nigeria’s past and present—families entwined across continents, marked by the echoes of colonialism, conflict, and economic challenges, finding temporary unity under the Super Eagles banner. For brief moments, they could rediscover their identity. For 90 minutes, Nigeria felt whole once more.

Some of the earliest Nigerian migrants to Britain have returned home, driven by the struggles of racism, feelings of isolation, or a longing for their homeland. Others have chosen to stay and fashion their lives in London. My father opted to return to Nigeria, while many of his peers remained.

Those of us born or raised in London have developed a deep affection for this place we have come to call home. Here, throughout the years, we’ve marked births, celebrated birthdays, and mourned the departed. Some have begun new families, ushering in a second generation of British-Nigerians. We’ve experienced our first jobs and first loves, crafting a lasting sense of kinship and connection until, like me, we reach a point where London feels more like home than anywhere else.

The Nigerian populace in London has continued to surge, with the 2021 census recording 266,877 Nigerian-born residents in Britain, not including their children and relatives born here. This is thought to represent the largest Black population in the UK, with notable presences across nearly every borough. The local football leagues reflect this vibrant dynamic: British-Nigerians competing for various clubs throughout the city, each chasing their Premier League dreams.

Consequently, when international allegiance becomes a topic of discussion, footballers are presented with two choices: to represent Nigeria or to break new ground with England, navigating the delicate balance between heritage and home. In recent tournaments, the British-Nigerian representation within the England squad has intensified, with players such as Tammy Abraham and Eberechi Eze from south London participating, alongside Bukayo Saka. Dele Alli and Fikayo Tomori, both of whom rose through the ranks at Tottenham and Chelsea, have also made appearances. By wearing their jerseys, they embody the multifaceted narratives of migration and evolving identities. They carve out a space within the national team that resonates deeply with our experiences; the Three Lions are no longer a distant thought, now firmly rooted in our consciousness. Now, memories of moments that have shaped English football—like England reaching the semi-finals of the 2018 World Cup and advanced to the finals of Euro 2020 and Euro 2024—are linked to my identity.

For many, there is a profound sense of pride and affection towards a new wave of Black players navigating the complexities and challenges of English international football. Among these athletes, Bukayo Saka has emerged as the brightest star. Growing up in west London, he has been recognized as Arsenal’s most talented player in recent years, taking center stage for both club and country. His presence signifies the contributions of Nigerians to this landscape, subtly woven into the fabric of the narrative. During the BBC broadcast of England’s Euro 2024 quarter-final against Switzerland, the meaning of his Yoruba name was shared with the 16.8 million viewers, with commentator Guy Mowbray noting that “Bukayo” translates to “adds to happiness.” For the first time, Nigeria has been integrated into the core of the national footballing saga.

Yet, resistance persists. Following the Euro 2020 final, when Saka missed a pivotal penalty against Italy, he and other Black players faced severe racist abuse, a painful reminder of the fragility of the home we’ve carved out in London. The remnants of empire still fuel animosity towards our presence.

The “innit innit boys” have confronted their challenges as well. In the aftermath of Nigeria’s 2023 African Cup of Nations final loss to Ivory Coast, which I watched in a bar in east London, the British-born players faced abuse online and from politicians. Following the final, Nigeria’s sports minister John Enoh posed a question about the players born outside Nigeria: “Do they have the spirit, the fire of a Nigerian born in Nigeria?”

In moments like these, we face the stark truth: we are not entirely of that homeland, and our distance bears weight. Here, too, in these new lands, we must seek our sense of belonging again. And so, we turn inward, discovering what London has imprinted on us and what we have fostered within it. This journey of self-exploration and the quest for home is a nurturing of the spirit. It serves as a means of resilience—an acknowledgment of all who have made this journey and a homage to those who are yet to come.

*An earlier iteration of this essay appeared in Italian in The Passenger Londra, a book-magazine bringing together investigative journalism and narrative essays about nations and cities, published by Iperborea.*

*Discover our podcasts here and subscribe to the long read weekly email here.*